After working with style guides for 20 years, all I can say is they’re best used with a sense of humor. At worst, style guides can turn into editorial antagonists, freezing the well-meaning writer into one who doesn’t write at all. At best, they can offer a level of polish that I see in some of the best writing.

So let these “style moments” serve as a guide to creating consistency in how you format your writing. Because when we give readers irresistible, exciting writing in a consistent form, we give them a chance to stay engaged.

Today we’re looking at the five most common hiccups I see in essays. We’re going to look at quotations, titles, parentheses, en-dashes and em-dashes. I’ll be using Strunk & White’s Elements of Style as a launching point, and I’ll also pull from my years as an editor to bring clarity where Mr. Strunk offers very little. Use this post as a cheat sheet of common places and ways to use these elements, but if you want a definitive guide, you can buy Strunk & White’s Elements of Style here. (That link helps support The Editing Spectrum.)

Quotations

If you’re writing on Substack, incorporating other people’s words into your work is a great way to create a sense of balance—and one of my favorite ways to show instead of tell. And because dialogue is such a powerful tool in any writer’s arsenal, knowing how to format quotes is important. Also, when do you quote versus attribute versus summarize someone’s thoughts? Keep reading to learn more. If you’re really trying to up your game, you can grab the latest edition of The Associated Press Stylebook: 2022-2024 (the one journalists and all major press outlets use), which will bore you to tears and also offer a fuller education with its miles of guidelines on quotations.

Let’s start with a review of the basics.

Where does the comma or period go when a sentence ends in a quotation?

A: It’s enclosed within the quotation mark.

Anne Lamott says, “Hope begins in the dark, the stubborn hope that if you just show up and try to do the right thing, the dawn will come.”

Where does a comma go in a series of quotes or titles?

A: Also inside the marks, “though logically it often seems not to belong there,” according to Strunk & White.

“Hamlet,” “King Lear,” and “Much Ado About Nothing” are some of William Shakespeare’s most recognized works.

Two common settings when quotations aren’t necessary

When a quotation is introduced by that, it’s considered “indirect discourse” and doesn’t require a quotation.

She said that the books would be ready by Thursday.

When using phrases that most people are familiar with or expressions, quotes are also unnecessary.

Should I quote them or summarize what they said?

Context is really important when considering when and how to summarize what someone said in your work. The lines get blurry when we cross into memoir since quotes are being offered from the memory of the author themselves. But if you’re interviewing someone for information to incorporate into an essay, quoting them indicates to readers that this sentence came out of their mouth directly.

If you’re using quotes around someone’s words, make sure you are quoting them accurately.

If you’re not fully confident that you heard their phrasing precisely, consider using a partial quote while summarizing what the information conveyed.

Quotes need to count. They should expand on the information in the story you’re telling. For example, I wouldn’t quote someone in a story about gardening: “I think the roses look nice.” This is easily summarized into a paragraph about other things the source enjoys about gardening.

Quote someone when they say something of significance that can’t be easily summarized in a paragraph.

Go-to phrases for quotes

When you’re quoting someone directly, I err on the side of not adding adjectives or adverbs to the attributing phrase. For example:

“The room put a shiver in my spine before the police arrived,” said Mike Jones.

In this case, there’s no need to add embellishment after “said” because the content of the quotation is offering enough imagery. And I think writing should lean more on the content of the writing than trying to add flourish to a quote.

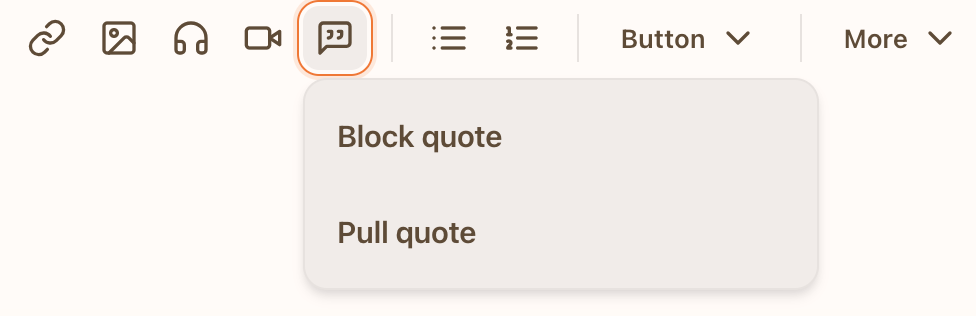

Formatting quotes in Substack

When you use the “block quote” or the “pull quote” feature in Substack, putting additional quotation marks at the beginning and end of the quote would be considered redundant. Using one of these features instead replaces the reader’s “heads up” that an official source or someone else’s words are now being quoted. Note: If you use one of these features on Substack and the quote includes a person speaking within it, use a single quote to denote where their words begin and end.

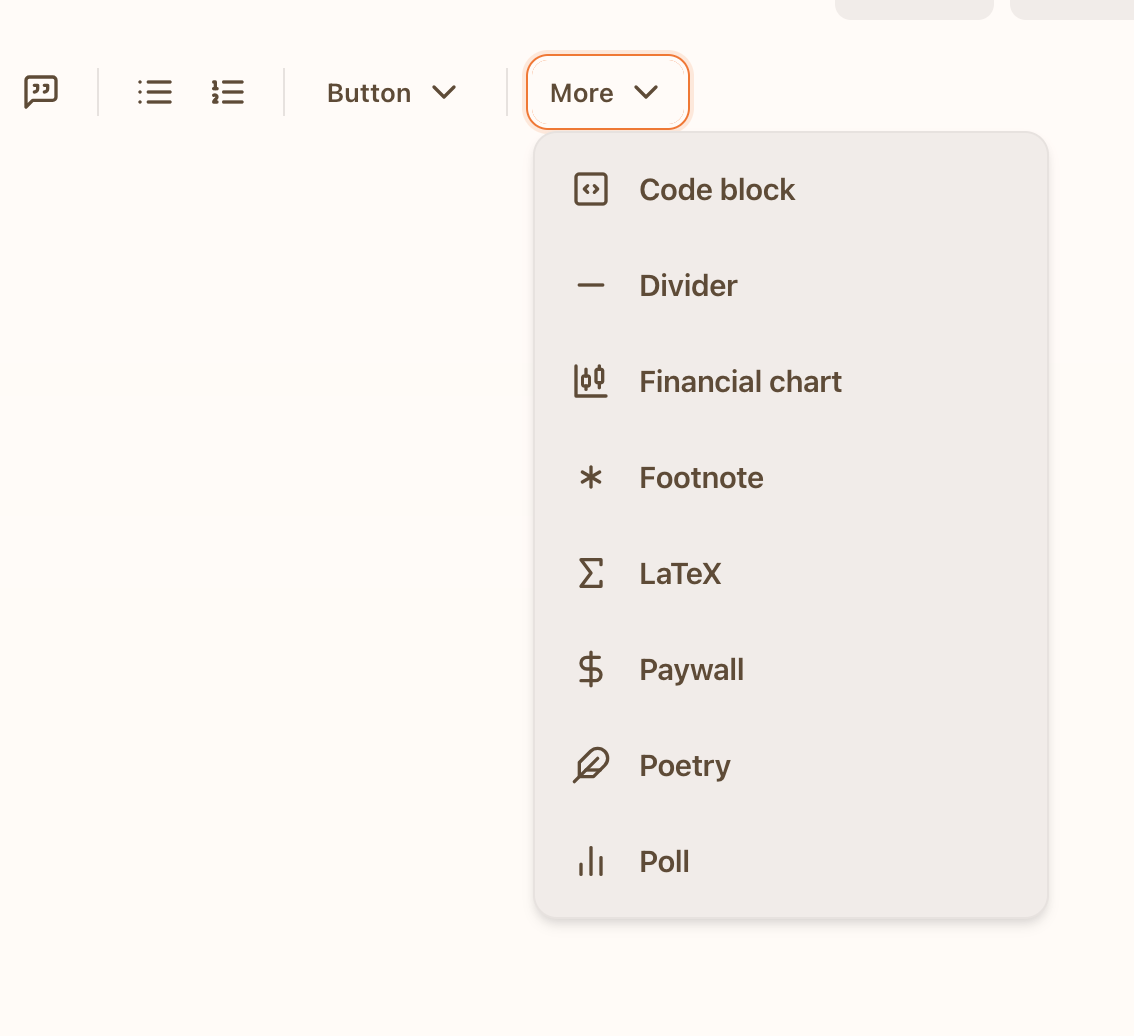

If you’re quoting a poem and want to get the spacing and formatting accurately reflected, you can alternatively use the “poetry” block.

Titles

How we format titles in our work should be introduced with a word of caution: Everybody has a preference and every publishing house has supreme domain over how they treat titles. So it’s important to know:

Some folks will italicize titles of magazines and movies, but want quotation marks for books.

Some folks will want quotation marks for all titles of literary or media work.

Some folks will want the first word of the title capitalized with everything else typed in lowercase. Others will want every word capitalized.

Some folks will flip flop back and forth, sending us all into dizzying circles.

I decided years ago it was best to let everyone have their own fun and not argue about the merits of something so trivial. For our specific work on Substack, I guide my editing clients to pick one convention for titles and stick with it. Strunk & White also have a simple word on the matter:

For the titles of literary works, scholarly usage prefers italics with capitalized initials. The usage of editors and publishers varies, some using italics with capitalized initials, others using Roman with capitalized initials with or without quotation marks. Use italics except in writing for a periodical that follows a different practice. Omit initial A or The from titles when you place the possessive before them.

The Buddhist Enneagram gave me so much to contemplate.

I just finished reading Susan Piver’s Buddhist Enneagram.

Psst: 🎥 Watch or read Susan’s Cave of the Heart interview here.

Parentheses

Here’s where things get pretty dicey in Strunk & White: parentheses. I had to re-read the two-sentence summary on p. 36 of my copy of the style guide no less than seven times to make sure I understood what they were delineating. So let me try to write it in a way we can all understand.

Parentheses deal with expressions that add to the substance of a sentence. These expressions would be too long or incomplete to denote with commas but not long enough to warrant an em-dash.

Parentheses should be used sparingly. I personally have a terrible habit of over-using them in my first drafts and have to slash them away in editing. Over-use of any grammatical punctuation mark “muddies the waters” of what should be tight, compelling writing.

Here are some examples of using parentheses well:

Emma enjoyed her vacation in Spain (especially the visit to Barcelona), where she experienced the vibrant local culture.

The CEO announced that the company had increased its revenue by 15% (compared to the previous fiscal year), marking a significant turnaround in its performance.

The teacher assigned the class to read three chapters of The Great Gatsby this weekend (chapters 5, 6, and 7).

En-dashes and Em-dashes

Chances are good you have an opinion about en- and em-dashes.

Most people tend to fall into one of two camps: they either use these punctuation marks incorrectly (interchangeably) or they use them way too much in their writing. I’m almost always in the latter camp. I love the feeling of squeezing in a good em-dash.

An em-dash feels a lot like my brain sounds—a complete thought followed by a trailing list of discoveries and observations. But of course, over-using any punctuation mark drowns out the chorus of good writing. (Did you catch the em-dash in the first sentence and the en-dash in the second?)

So let’s talk about how to use them; what the difference is between the en-dash and em-dash; and how to create them on your keyboard.

For starters, have you ever wondered why they’re called the en- and em-dashes? It’s because the length of each dash corresponds to the letter ‘n’ and the letter ‘m’ in a typeface family. There are, of course, so many typeface families now that do not hold to this standard! But when we were all plunking down our words with typewriters and using the same, standardized typeface, these dashes were the width of these letters, respectively.

They’re not interchangeable

The standard use for the en-dash is to denote a range inside a numerical value, like numbers or dates.

I’m available from May 5 - 10.

An em-dash, however, is used to “set off an abrupt break or interruption and to announce a long appositive or summary,” according to Strunk and White. The em-dash has a much bigger job to do for the eyes of our readers, and it’s important to let them create the “pause” in reading that you intend to convey. An em-dash is “stronger than a comma, less formal than a colon, and more relaxed than parentheses.”

A few examples of how to use an em-dash in your writing

The old farmhouse—weathered by time and neglect—stood silently against the backdrop of the setting sun.

He offered me two choices—stay or leave—and I had only a moment to decide.

She was determined to finish the marathon—even if she had to crawl across the finish line.

How to make the en- and em-dash on your keyboard

An en-dash is created by pressing the hyphen button next to the number 0 on any standard keyboard. It looks like this - .

Alternatively, if you are trying to add an em-dash to a sentence, here are the keys to hold down to do so.

» On a PC, you press the Ctrl key, Alt key, and the hyphen key (the same one next to the number 0).

» On a Mac, you press the option, shift and hyphen key.

» Edited to add: With thanks to

, I was today years old when I learned you can also double tap the hyphen key to create an em-dash. Though, this seems to be hit-or-miss if you’re leaving a comment on Substack. Thanks, John!Doing any one of these should give you the em-dash—wasn’t that easy?

As someine with an English degree from 15-35 years ago, and which of course used MLA, I loved this post! I think I mostly use these correctly, but I'm not always sure why, which often leaves me wondering. Interestingly, it wasn't until I was teaching a business writing course at a community college that I truly learned the ins and outs of commas--and that was only because I asked a retired high school English teacher to break it down for me. I almost regret it because I spend far too much energy now making sure my commas are correctly placed 😂. Nonetheless, hooray for all posts teaching proper grammar and punctuation!

Thanks Amanda, useful stuff. As a Brit, I find myself tripping up over some of these. Where Americans will put the period inside the quotes, Brits will put the full stop inside the inverted commas.

In the Substack post or notes editor on a PC or Android device (and probably a Mac?) you can make an em-dash by hitting the hyphen key twice. It doesn't work in comments though!