Tara McMullin on Marketing Your Substack (Without Watering Down Your Art!)

This classic marketing framework is a powerhouse tool that can help you reach more readers

Today I’m featuring an article about marketing your Substack without watering down your art. I first met

through a great comment she left on one of my essays. I quickly clicked over to her Substack, What Works, and discovered that she’s autistic like me and is a voracious writer, learner, podcaster and communicator. (She even wrote a book, “What Works,” published in Nov. 2022 by Wiley.) Tara is constantly tackling topics that feel intrinsically insurmountable to me. But, no surprise, she is a master chef in the writing kitchen. I’m so glad she’s sharing some knowledge with all of us today from her previous special interest (marketing). If you’re ever searching for a helpful filter to run your writing through, then this piece is for you. I love that at its core, this marketing advice is rooted in empathy and thinking more intentionally about reaching readers.Marketing Advice That’s Great Writing Advice, Too

by Tara McMullin of

The best marketing advice I ever received was to first consider what my ideal customers know right now. It turns out, this is excellent advice for writers who want to reach more readers, too.

I'll prove it to you. I could have started this article by writing: "The customer awareness spectrum is a helpful tool for writers." But if I'd done that, you likely would have hit the words "customer awareness spectrum" and stopped reading. Marketing jargon tends to do that to people.

But instead, I described what the customer awareness spectrum is without naming it (i.e., a way to think about what my ideal customers know right now), and then I threw in something quite familiar (i.e., how to reach more readers).

I mean, here you are, reading a Substack entitled "The Editing Spectrum." It's easy for me to imagine that something you know right now is that you want your writing to reach a wider audience. All you need to know in the first couple of sentences is that I know you know that—and I have some advice to share. You don't need to know who I am, what tool I'm going to help you use, or how I came to be writing this article for Amanda.

By the way, my name is Tara McMullin, and I'm a writer, podcaster, and producer. For a long time, I was also a marketer. In fact, marketing was a special interest of mine for many years. Today, I prefer not to think of myself as a marketer, nor do the ins and outs of marketing hold much interest for me anymore. But what I’ve found is that by employing the skills I learned as a marketer, I can bridge the gap between my special interests and my readers interests.

A good marketer obsesses over the people she wants to reach.

She thinks about both their inner and outer lives. And she tailors what she creates to perfectly reflect their needs and desires. Writing is inherently more personal—even when it’s not personal writing. And so obsessing over our audiences the way a marketer does can degrade the power of that personal quality. Like Amanda recently wrote:

“A lot of us lost our way in the drive for readers, clicks, attention, validation and so on. And in the process, the quality of all writing everywhere seemed to diminish.”

When I encourage writers to think about their readers or even how to reach more readers, I’m not talking about changing their art. I’m talking about accessibility—the ability of a reader to enter and engage with a piece, to access the idea or story the writer is trying to convey. And while accessibility might not be the goal for every writer, it is a goal for those of us who want to reach more people with our ideas and stories.

To me, the accessibility of a piece isn’t an objective function of vocabulary, syntax, or argument. Accessibility is the willingness to relate to your reader, to take on their perspective, and to see your work through their eyes at some part in the writing or editing process (without imagining them as hostile to your project). Accessibility acknowledges the connection between you, what you write, and who reads it.

Now that we've gotten that out of the way, I'd like to share how thinking about your readers in this way makes your work relevant to more people without watering down your art.

Who we write for determines who will read what we write.

There is absolutely a place for writing that's all mine, something that only I and an inner circle of readers will ever engage with. But if I want more people to read my words, hear my stories, or think about my ideas, then I need to make sure that what I'm writing is not only relevant to them but, in some small way, familiar to them.

While adventurous readers might click a link or start an article that feels completely foreign to them, most readers need something to draw them in. They need a point of connection with a piece. That connection might be a relatable story or an unexpected historical tidbit about a contemporary phenomenon they're familiar with. It could be a bit of intrigue that turns conventional wisdom on its head. Or it could simply be an acknowledgment of a fear, hope, or question that's on their minds. If I do the work to find the connection, then I can write about whatever I want and trust that my ideas will reach a wider readership.

The customer awareness spectrum can help us think through how we might make that connection for readers.

What is the “customer awareness spectrum?”

Marketers use the customer awareness spectrum to think through what kind of messages need to be delivered to a potential customer and when.

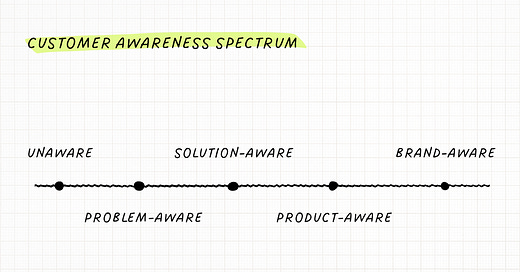

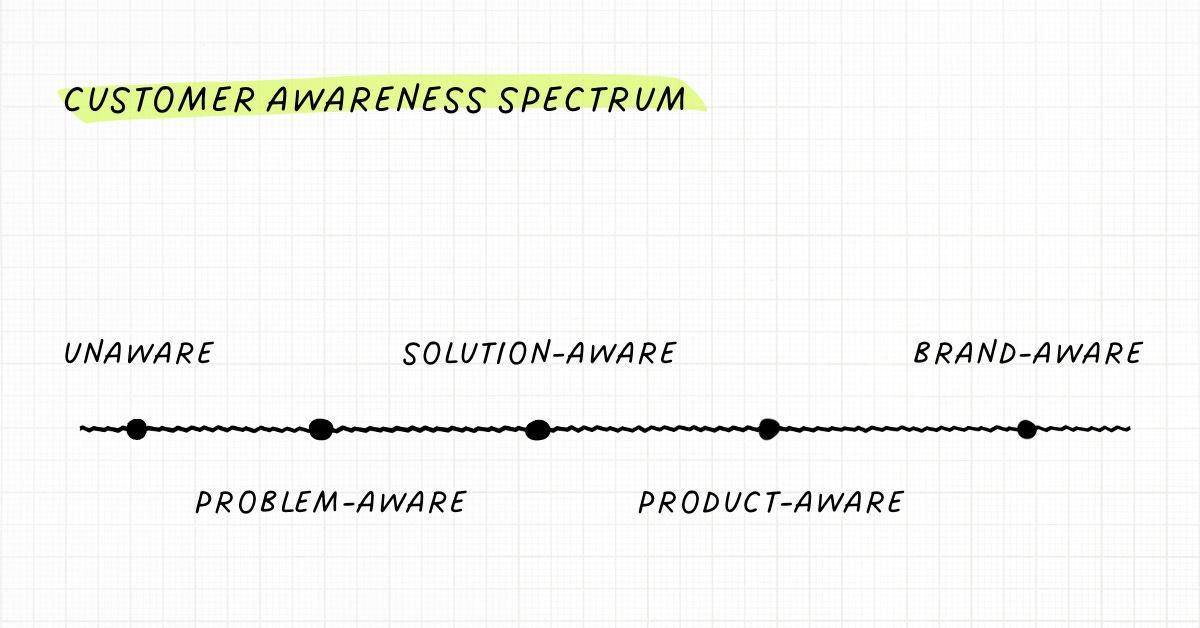

Marketers will break this down into 5 stages:

Unaware: they know about other things

Problem-Aware: they know about their problem and its pain points

Solution-Aware: they know about a possible solution

Product-Aware: they know about the particular solution that you offer

Brand-Aware: they know the brand and what it's about

What does this look like in practice? Allow me to demonstrate using Jones Road Beauty’s Miracle Balm. This product, designed by makeup artist Bobbi Brown, is sort of a tinted waxy substance you can put on your face to make it “glow.” Here’s how I would message it:

“5 Summer Beauty Trends Show Off Your Inner Glow” - this would make for a great blog post for attracting Unaware prospects and introducing them to the product

“Tight on time? This can cut your mirror time in half!” - I could see this as a TikTok or Reel aimed at busy Problem-Aware prospects

“3 Essential Additions to Your No-Makeup Makeup Routine” - again, a great blog post or email for the Solution-Aware prospect who knows they’re into the no-makeup makeup look

“How to Apply Miracle Balm for a Summer Glow” - a quick tutorial for Product-Aware prospects, also good for encouraging repeat buying

“From the makers of Miracle Balm…” - once a customer loves your brand or your product (Brand-Aware), messaging can be very direct even when you’re marketing something else

You probably noticed that the first three messages were indirect. That is, I didn’t name the product at all because they don’t care about the product yet. It’s not what they know right now—and so it’s not going to attract their attention.

The second two messages are direct. They’re aimed at people who already know about the product.

Now that you've become a master of marketing messages, let's talk about how this applies to writing.

Turning customer awareness into audience awareness

Since I'm more of a writer than a marketer these days, I think less about how to sell my products and more about how to communicate my ideas. For me, that means introducing people to subjects from economics, philosophy, and critical theory that they have often never heard of. I know how those ideas are relevant to them and their daily lives—but they don't.

Earlier this year, I created a series of essays and podcast episodes about economics. I wanted to look at common questions about contemporary work and culture and use economic concepts to gain new insight into how to answer those questions. Most of the people I wanted to reach with this series don't read or listen to economic theory for fun. In fact, I didn't want to write to an audience who readily thinks about economics.

In the first installment of the series, I decided to cover "opportunity cost." Opportunity cost is a common entry point to economics because it invites us to recognize multiple ways we might allocate our resources—even when it seems like there aren't options. One way to approach writing about opportunity cost would be to lead into it with a sort of Solution-Aware approach: "How to Use Opportunity Cost to Make Better Decisions." This would be a good way to lead into my essay if I was writing to an audience who was already familiar with the idea of opportunity cost or if I knew they were open to engaging with unknown material. And certainly, a segment of my audience fits those criteria. But I wanted to make sure this installment reached as many people as it could.

To reach more people, I could use a lead-in that aligned more with a Problem-Aware approach: "Have trouble making decisions? Here's how to weigh your options." With this kind of headline, I acknowledge a problem a wide group of people have, and I promise a solution without naming it. I name an anxiety and dangle relief in front of readers like a carrot. This is also a good approach—most people would probably identify as struggling with decision-making from time to time. But I knew I could go one step further.

I could reach Unaware readers.

Unaware readers, you may recall, aren't affectless blank slates. They're aware of something—just not what we might want them to be aware of. Often, their awareness lands on misidentification of the problem. They think it's X, when really it's Y. For this piece, though, I realized that my readers were too close to the problem to realize what it was. That is, they had fixated on one particular dilemma rather than seeing this issue as part of a larger system.

Many of my readers—and many of my potential readers—feel all sorts of anxiety about social media. The questions about social media and its future crowd out more comprehensive thinking. They can't tell what they worry about when they worry about social media or whether there might be other options available to them. This became the perfect lead-in because it gave me a way to speak directly to something they were keenly aware of, and it was a perfect scenario for using opportunity cost to explore other options.

Plus, I had a story that could bring opportunity cost to life. My friend Hillary Rea, who helps leaders tell powerful stories, quit social media entirely starting in 2020 and culminating in 2022 with the deletion of her LinkedIn account. For Hillary, business was better than ever. By demonstrating what she spent her time on now, I could illustrate the options my readers have. In the end, the piece was about whether or not to quit social media—but it was really about how easy it is to discount the many options we have and how opportunity cost gives us a framework to engage with those options.

The final piece, which also included a digression into what the field of economics actually is, was very well-received. Many people told me that it helped them make the leap to marketing minus social media. And still others said they got a new way of thinking about other decisions that had confounded them. I can't know this, but I suspect that the piece wouldn't have had nearly the impact had it been straightforwardly about opportunity cost and decision-making.

Audience awareness helps with structuring a piece, too

Understanding what my readers are familiar with at a moment in time not only helps with figuring out a headline and lede. It also gives me a spine of structure that I can build my essay from.

In marketing, the customer awareness spectrum guides messaging from Unaware to Problem-Aware, Problem-Aware to Solution-Aware, and so on. In my writing, I think of building out an essay from Familiar to Unfamiliar. This could mean starting with something concrete and then zooming out to cover topics that become more abstract. Or, it could be starting with a familiar question and using relatively unfamiliar stories or concepts to explore the answer(s).

For example, I wrote a piece about refund policies in which I covered both the origin story of the money-back guarantee and the existential question of whether the customer is a friend or foe. I think that the uneasiness of asking for a refund is a pretty universal experience. Whether you're returning a t-shirt to the Gap or asking for your money back on a pricey online course, we all have some experience with returns. And for my readers, they also all have experience with being asked for a refund—which, frankly, sucks.

So I began with that universally relevant experience.

From there, I structured the essay to reach out for unfamiliar information or ideas and then lead back to the more familiar core. First, I told the story of Josiah Wedgwood, the founder of Wedgwood Ceramics. He's a fascinating character—a bit of a radical and heavily involved with the English abolitionist movement. He also single-handedly pioneered many of the marketing techniques we take for granted today—including the money-back guarantee.

I let myself indulge in Wedgwood's story early in the piece because it was a fun way to create context around familiar issues, namely that business is about building relationships. Then, I brought the story back around to refund policies. From there, I stretched back to the unfamiliar by examining the consumer psychology and marketing strategy behind today's most generous refund policies. The familiar grounded that section by prompting the reader to consider their own experiences within that framework.

Next, I made the familiar unfamiliar by incorporating an interview with another writer in my space. She has her own theories about refunds, which go against the grain of conventional wisdom among my readers. What we talked about was familiar, but the way we talked about it was unfamiliar.

Finally, I incorporated more abstract concepts like risk, trust, and generosity before applying them to the familiar core of the piece. In the end, the structure of the piece looks something like this:

Lede: Refund policies for online businesses are adversarial. The customer has become the enemy.

Scene 1: Josiah Wedgewood and how his now-ubiquitous marketing tactics were all about customer relationships

Digression 1: Current state of retail refund policies, acknowledging refunds as an integral part of building customer trust

Scene 2: Two ways of thinking about the risk of error inherent to refund policies and how that risk impacts customer relationships

Digression 2: Tie retail refund policies to refund policies in online businesses, interview with Regina

Scene 3: Acknowledge the more existential risk we face as small business owners—and how refund policies can be a microcosm of that risk

Digression 3: Brief history of "buyer beware"

Scene 4: Is the customer friend or foe? The ethics of refund policies (and beyond)

Conclusion: 3 suggestions for creating more fair and ethical refund policies

As each scene in the piece progresses, I push and pull on familiarity (or unfamiliarity) to keep the reader with me while I introduce new ideas.

That's just one way to structure a piece using audience awareness. Your piece might lend itself to something more akin to the marketing framework. You could take your readers from Unaware to, say, Question-Aware, then from Answer-Aware to Application-Aware. Or, your piece might look more like a traditional story arc, but instead of rising action, climax, and denouement, you take them on a journey from Familiar to Increasing Unfamiliar and back to Familiar again.

So how do you figure out what your readers know right now?

Speaking of getting back to what's familiar, at the very top, I said that the best marketing advice I ever received was to start with what my potential customers know right now. And when it comes to writing, I want to think about what my potential readers know right now—what's already familiar to them—so I can introduce something that they don't already know.

But how do you figure out what your potential readers know right now? There's a tool that I come back to over and over again to accomplish exactly that: the perspective map (or empathy map). When I consider who I'm writing for, I reflect on what they're thinking about. I imagine their inner monologue, the questions that nag them, or the challenges they wish they had a solution to. I also think about what they're doing on a regular basis and how that behavior may impact their experience of the world. I originally picked up this skill to navigate the world as an autistic person—long before I knew I was autistic. But it turned out to be a real superpower when it came to marketing and writing.

This skill is called perspective-taking, a concept from the world of design that invites the designer to take the perspective of the person who will use or encounter the thing being designed. When I consider what my reader says, does, thinks, and feels, I get to know them better—and have a better idea of what they need from me or my ideas. I get familiar with what they're familiar with in order to connect my thoughts to their lived experience.

Perspective-taking sets you up for using audience awareness to reach more readers.

To get give it a go, consider the topic you're writing about or the story you're sharing. Then ask yourself:

What are my readers saying about this? (e.g., "I can't believe how Elon Musk is tanking Twitter!")

What are they doing about this? (e.g., asking friends where else they're connecting with fellow writers and readers)

What are they thinking about this? (e.g., "I think social media might be dying—but if it does, how will I share my work?")

What are they feeling about this? (e.g., anxious, fearful, a little relieved)

For each question, I entertain all of the answers that float through my head. When I was first getting the hang of this, I'd write down my answers in a table like this:

Now, though, perspective-taking is more of a cognitive reflex that occurs whenever I think about how to ensure my piece is accessible to my readers. Once I've answered the perspective map questions, I have a pretty good idea of where my readers' heads are at. I have a sense of their emotional state. And that's fertile territory to write (or edit) from.

From here, I can think about the interplay between familiar and unfamiliar and the order in which I might introduce new concepts to reach my conclusion. I can demonstrate to my reader that I get where they're at and that I have something to offer. And even when I'm not doing service journalism or writing an educational piece, I can ensure that what I produce feels relevant even if my approach is profoundly personal or distinctly unfamiliar.

By taking special care to make my work feel relevant, not only do my readers engage my work more deeply, but they share my work with others who will also find it relevant. It might take time and energy to ground my work in something familiar, but that time and energy pay off in new readers every time I publish.

Got a question for Tara about a piece you’re writing now?

She’ll be jumping into the comments today to answer your questions!

Tara I absolutely loved this! I'm a marketer and I so thoroughly enjoyed this deep-dive. Thank you! My question is: will you please tell the people (we're all clamoring, we need to know!) what title you decided on after ditching "Have trouble making decisions? Here's how to weigh your options."?

Ah this was helpful. A reminder that I'll be introducing readers here to my books at some point and I'm currently assuming most of them don't know about them. So I can talk about what I read and why and why I wrote them as a way to lay the land and begin to increase awareness.