It is the kokoro that allows us to see, respond to and create beauty

Beth Kempton joins Cave of the Heart and answers five questions on self-trust

Cave of the Heart is an interview series where writers trust-fall into the depths of inner-knowing, creativity, and the craft of writing. Are you ready to get curious about the cultivation of self-trust, give a warm nod to our child selves, and celebrate inspiration in all forms? Come with us into the cave of the heart.

is a Japanologist and a bestselling self-help author and writer mentor, whose books have been translated into 28 languages and recommended by the likes of TIME Magazine, British Vogue, Psychologies and as an Apple Must-Listen audiobook. Beth has had a quarter-century love affair with Japan, and has made it her work to uncover life lessons and philosophical ideas buried in Japanese culture, words and ritual. Beth has two degrees in Japanese, including a Masters in Interpreting & Translating. She is also a qualified yoga teacher and Reiki Master, trained in the Japanese tradition in Tokyo.Her sixth book, Kokoro: Japanese wisdom for a life well lived (out April 2024) is a follow up to her earlier bestseller Wabi Sabi. If you’d like to pre-order Beth’s next book (and receive a free gift for pre-ordering), use this link if you’re in the UK or this link if you’re in the United States (it includes free international shipping from Blackwell’s).

Describe the setting where you’re answering these questions.

I’m at a café in the Roman city of Bath, in England, perched on a banquette the colour of fudge. The shiny yellow Formica table is at odds with the weather and my mood. I am waiting to check in to the small flat I have rented nearby for the weekend, so I am surrounded by stuff – a small wheely suitcase, a rucksack, a yoga mat bag padded out with all the clothes that wouldn’t fit in my case (because I filled that with books), and a stack of notes for the writing project I have brought with me. It’s noisy here — a coffee machine is hissing, a kitchen alarm is beeping, and there are separate and hopeful conversations about cancer going on at the tables on either side of me. The air is a heady mix of 90s pop music, evaporating rain, and the scent of coffee cake. It’s not my normal scene, but I kind of like it.

Childhood

Q: Given a choice, were you the child who would run barefoot outside or were you inside reading?

A: I have boats in my blood, salt in my veins and many years’ experience of kicking a football around in the garden with my brothers. But truly, I am a child of words — a house full of books, a street full of stories. I come from roast chicken on Sundays and teapots of tea served up with love by a teacher and a dreamer. I come from effort disguised as luck and enterprise, from a rollercoaster of having and not having, of knowing and not knowing, but always hoping.

As for so many people, books were where I went to escape the everyday chaos of childhood and the teenage years. I had a friend who loved books too, and we used to have reading sleepovers, where we’d stay up as late as possible with our books, silently reading side by side, and sharing midnight feasts of jammie dodgers and strawberry toothpaste.

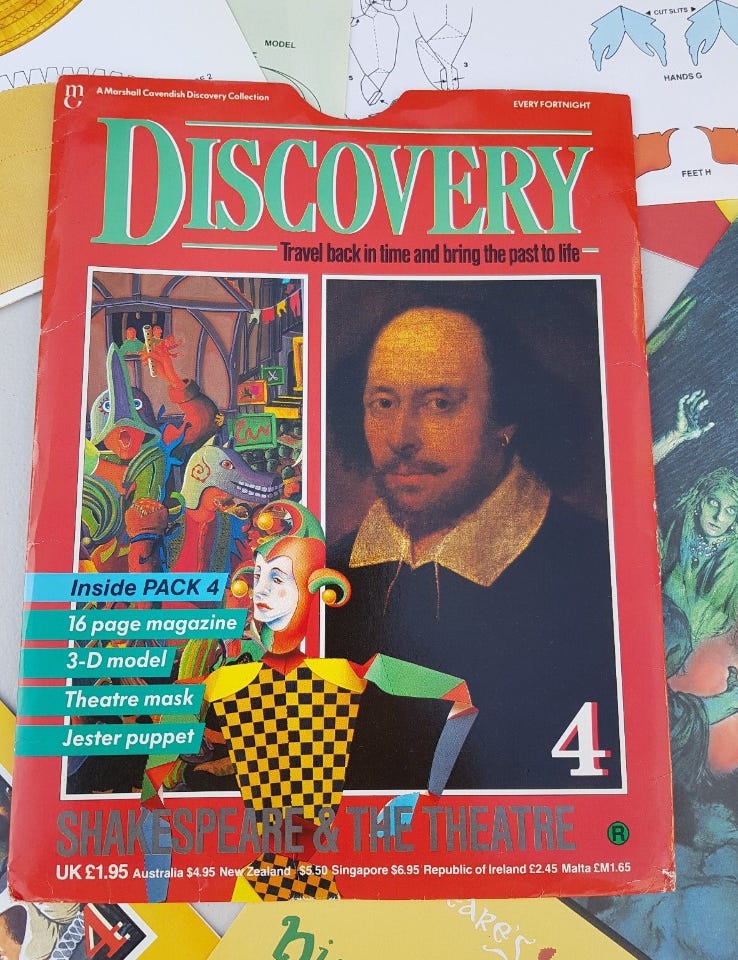

I read anything – Nancy Drew, Malory Towers, Sweet Valley High, and anything by Roald Dahl and Judy Blume. Back in the late 80s we used to get a fortnightly magazine called Discovery which taught us about a different historical period in each issue, and included a related project to make, like a 3D paper model of the Globe Theatre for the Shakespeare issue.

My brothers and I were allowed to walk ten minutes to the newsagent together to collect it on Saturday mornings (and spend a few coins on penny sweets). I think this might have been the first time I associated reading with independence.

At home we had books in every room in the house, in the hall and on the landing. My mum read all the time. She was a primary school teacher who believed that there are few things in life more important than education. I actually just wrote about this in my new book, when I was reflecting on the many ways my mum influenced my love of books and words. On rainy days, she would go to the cupboard under the stairs, reach through the heavy winter coats and pull out a black bin bag. It was full of books wrapped like gifts, a lucky dip with stories for a prize. I still remember the feeling of reaching in and choosing one.

Later, when I was getting ready to head off to university to study Japanese, she came with me to London, even though she was scared of the underground. We spent hours in the Japan Centre bookshop, gathering everything on my reading list and sharing the excitement of a new beginning.

A few years ago, Mum spotted a woman holding a copy of Wabi Sabi in Waterstones, considering whether to buy it. She later relayed how she had blurted out, “My daughter wrote that book!” And then had no idea what to say next. I hope she knew that the book in the woman’s hands only existed because of the love of words she had instilled in me from a young age.

Influences

Q: If you had to choose one person from your past that most influenced who you are today, who would that be and why? This can be a person from history, an animal, a fictitious character in a book, TV or movie.

A: I have had many, many teachers (which is why I love writing the Acknowledgements section of each book), and my mother influenced my life in so many ways (see above), but my immediate response is to say my seventeen-year-old self. She took an action that was astonishingly bold.

Until I was seventeen, I was on a track advised by others: to do Economics at university and then become an accountant because it was a stable career and I could have a nice house. All the people I trusted recommended it, so I made it my plan. I even have a work experience rejection letter from a local accountancy firm dated 1988, when I was 11. But then in that magical summer of seventeen, I found myself on a sail training yacht, in the middle of the Bay of Biscay, racing from England to Spain.

A couple of days into the race, after long night watches and a storm which had me convinced we were all going to die, a blue sky opened up and we sailed into an area of complete calm. I was at the helm alone, while everyone else slept below or lazed on the foredeck. I felt like I had an entire ocean to myself, with only a chirpy school of dolphins for company. As they splashed around the bow, I looked out to sea and let out a deep, contented sigh.

The sun was shining and there was so much space all around. I felt as if I had been holding my breath for years, and only then exhaled. In that moment I realised I didn’t want to be an accountant. I had absolutely no idea what I wanted to do with my life (which was kind of exciting) and I wanted to feel how I felt in that moment for the rest of my days. I felt happy. I felt deeply connected to the planet, extended beyond myself, part of the waves and the sky and the beauty of it all. I felt called to explore. I was out there dancing with the dolphins. I felt free.

In that flash of clarity, I knew I wanted a life full of adventure. This revelation was at once terrifying and electrifying, and I had no idea what to do next.

Opting for a degree that would give me a year abroad seemed like the answer. I loved the idea of connecting with people in far-off lands, and discovering more about the world. However, I hadn’t studied any languages at A-level – a prerequisite to all modern language degrees at the time. Except, that is, if you chose something relatively obscure (in terms of course registration numbers) and insanely difficult, like Chinese, Japanese, Russian or Arabic. Although popular now, in 1994 learning these languages was the domain of talented linguists. I couldn’t speak a word of any of them; I could hardly even speak French. So I did what any slightly reckless teenager might do and used the nursery rhyme ‘Eeny Meeny Miny Moe’ to make the most significant decision of my life. I landed on Japanese, and my life trajectory shifted.

When I returned home and casually mentioned this bombshell to my parents, instead of trying to dissuade me, my mum took me to a bookshop. We went to the travel section, which only had a handful of books about Japan. I picked up a travel guide (the Insight Guide to Japan – I still have it) and it fell open to a photograph of a pagoda covered in snow. Something inside me fizzed. Later, I stretched out on my bed and thumbed through every page.

On one page, a gently curving red bridge crossed a rushing river. On the facing page, a long line of moss-covered statues sat in a shady forest, waiting. There was talk of volcanoes, rice fields, tropical islands and remote shrines. I had only ever been to France on a school trip. Japan was a world I knew only in my imagination, and yet as I lay there poring over a photograph of two silhouetted figures sitting in quiet contemplation in a shadowy temple, looking out over a bright garden beyond, I sensed something that has never left me. A hidden truth about what it means to live well.

This pull towards Japan has been a siren call throughout my adult life. In answering that call I have been blessed by many encounters with people whose ways of seeing and being have influenced the way I live for the better. So I think it’s fair to say that the seventeen-year-old version of myself who had that burst of courage to change course has influenced both the life path I have travelled and the person I have become, and am still becoming, along the way.

Creative Spark

Q: When you get an idea for a new essay or project, what does your first instinct look, sound or feel like?

A: It’s an utterance of the heart, for sure, and it is usually followed by a sense that my eyeballs have been washed — everything is more vivid, and I can see connections everywhere.

What I have come to see over the years though, is that I have often been carrying the essence of the idea before I recognise it as an “idea” – as if I know before I know. My notebooks are full of evidence of this. When I was writing The Way of the Fearless Writer, I had cause to go back through more than 120 of my journals stretching back to my teens, and I found references to the terms wabi sabi and kokoro from entries several years before I realised those were the titles of books I would one day write.

Once I have acknowledged an idea, and sensed a deep pull towards it, I make notes of all the connections and related signs I notice, which come thick and fast once I start looking. I often see certain motifs everywhere.

With my first book Freedom Seeker, which has the metaphor of a bird running through it, and a bird on the front cover, it was all about feathers. One morning, when I was feeling overwhelmed by the amount of material I was trying to organise and had lost all sense of what the book was actually about, I opened my front door to hundreds of feathers on the front lawn. Walking to a café to meet a friend I was passed by a woman with a shaved head and a giant peacock feather tattooed across her scalp. My friend arrived wearing a feather-print dress. The barista had feather earrings on. I noticed when she was trying to shoo a trapped bird out of the café door. By the time the truck drove past the window with a giant feather painted across its side, I was laughing. You just couldn’t make it up. Each occurrence was a much-needed reminder of what the book was about: the journey from trapped to free, of taking flight and soaring. I just had to stay focused on that and it would all come together.

You can read whatever you like into signs, but I believe that every sign you notice is proof that you are waking up.

A similar thing happens when I am deep in an idea, trying to figure out how to structure it into a book. For me writing books is largely about asking questions and then going in search of answers, which often don’t arrive in a tidy fashion, so I usually work on the individual pieces of the jigsaw without knowing exactly what the image on the front of the box looks like.

My notebooks tend to be a combination of ordered pages of tiny writing (or sometimes crazy scribbles, depending on how I am feeling at the time), and chaotic visual pages of sketched out ideas. It goes on like that for a while (sometimes years) and then a day comes when all the pieces suddenly fit together and the overall picture becomes clear. That realisation is often how I arrive at the structure of my books.

As soon as I know what that structure is, I can’t unsee it. It’s almost as if it has been there all along, and it is so obvious then — as if it couldn’t be anything else. Looking back through the individual pieces I have been working on for months and years previously, I can see hints of it everywhere, and retrospectively notice more patterns and correlations between the pieces. In my experience this can’t be rushed or forced. Time is the alchemist which turns all the disparate pieces into the clear picture which guides the shaping of a book.

I should mention that without exception, my structure always collapses in a major way about four weeks out from finishing the manuscript. Not entirely – the main idea remains, but often I realise that I have put the pieces in the wrong order or missed an important detail. I might move a chapter, or an entire part of the book, and then suddenly I have the feeling of knowing that it is finally just right.

This kind of knowing is actually something I have explored in depth in my new book, KOKORO: Japanese wisdom for a life well lived. “Kokoro” is a beautiful, untranslatable Japanese word with many shades of meaning but it approximates to “the intelligent heart.”

It is through the kokoro that we see, respond to and create beauty. We can’t think our way to our best writing or other art, or to our most aligned life path, for that matter. We have to feel our way there. Of course we can be thoughtful and skillful about polishing what we have written, but the raw and wild beauty that spills from our veins and pens is rarely something we have intellectually “thought” would be a good idea. Perhaps this is why our best writing often feels slightly dangerous…

Writing Process

Q: What does your writing life look like today, and can you compare/contrast it to 10 years ago?

A: Ten years ago I was a couple of years into setting up my business, Do What You Love, having left the male-dominated world of international football. This was partly inspired by an experience on an art retreat in California, which made me want to work with and in service of creative people, particularly women who have had their dreams crushed for whatever reason, somewhere along the way. For the first few years I mostly produced retreats, workshops and online courses (back in the early days of blogging) to help people navigate change, be more creative and make a living doing what they love.

I have two small children, run my own business, and I have carried so much self-doubt that I’m still amazed that my words made it to the printed page.

I have been writing for as long as I can remember, but I did not become a fearless writer until the age of 39 when I was cracked wide open by an extraordinary experience with a black hawk eagle in Costa Rica. (That’s a story for another day!) Until my first book (Freedom Seeker: Live more. Worry less. Do what you love.) came out, my work kept me behind the scenes, and I was wholly unsure about stepping in front of the curtain to share personal stories with the world. But the book demanded to be written, so I had to find a way.

Before that I was plagued by fear and self-doubt, like many writers. It was so bad it almost stopped me finishing Freedom Seeker. In fact, it was so bad it nearly stopped me starting. The fear manifested as obsessive perfectionism and a need for control. The more I tried, the harder it got. Until it all got too much, and I finally surrendered. That’s when the whole book came flooding out.

It took me several years of writing books to realise that I hadn’t just found a way, it was a Way — what I call the “Way of the Fearless Writer” and explained in the book of the same name. This “Way” is a radical departure from standard advice about creative success, which usually involves painful effort, the pursuit of perfection and the tyranny of critique. Rather it’s about uncovering another way to thrive: a path of ease, discovery and wonder.

That first book was published a few weeks before my 40th birthday. I am 46 now. My six books have been translated into 28 languages. I have a beautiful writing community. I host the Fearless Writer Podcast. And more than 30,000 people have taken my online writing classes. To be honest, it blows my mind. There are many reasons to love this work, but one of my favourites is that it shows my daughters we can take what is in our heads and hearts and then turn it into physical books in our hands, food on our table, and an interesting life.

Resources

Q: What’s one surprising or unlikely resource that you turn to again and again to bolster your writing life?

A: Poetry. There is so much beauty tucked into the pages of poetry books, and one of my favourite ways to begin a writing session is to light a candle, read a poem aloud, and then just start writing, and see what comes. There might be a single image in the poem that has sparked something, or perhaps it has a particular rhythm that sends my words in a certain direction, or a memory bubbles up and I write that. Sometimes I just linger in the space left behind by the poem, watch the sun rise, and exhale ink onto the page.

Join Beth in the comments!

Beth wisely says that “every sign you notice is proof that you are waking up.” What sorts of signs do you notice (if any) in your own writing practice?

When Beth says, “We can’t think our way to our best writing…” how do you interpret that to your own writing life? What would it look like to bring your best writing to the world?

Beth, you are a great storyteller, which is a role I have aspired to all my life. Long before I aspired to be a writer.

Thank you for all of these stories. They were the visceral, human touch I needed this morning.

What an amazing story in itself, Beth. All I can say is thank goodness you didn’t become an accountant. I escaped a soulless existence of ‘delivering shareholder value’ just over 10 years ago. Now to find the courage to truly call myself a writer!